Introduction

One of my graduate courses this semester is “Literary and Cultural Theory.” Immersion in manifold theories (Saussurean structuralism, Derridean poststructuralism, psychoanalysis, Marxism, and various critical theories—gender, queer, critical race, affect, and thing theory) has made the semester informative and intellectually stimulating. My first paper for this class (Ungilding the Lily of Lear’s ‘Love’: A Diachronic Endeavor into Différance) received marks that motivated me to return to it, further refine it, and now post it.

Of course, what was initially four pages has grown into something more. In addition to the academically inspired (required?) theoretical analysis, there are a few portions where I flex my philosophical muscles (sore or atrophied though they may be, depending on the depth of analysis). This is especially prevalent in Part Two: Defining Love. The meat of the original academic paper begins at the beginning and continues after Part Two. All exposition is in the spirit of precise, concise, accessible, and engaging communication of my considerations. Things are seldom as simple as they seem—I hope the methods I employ are articulated such that readers can apply them in their own analysis of endlessly significant stories.

The following paper is a diachronic endeavor into the différance that is the implied supplemental past of Shakespeare’s King Lear. Over the course of approximately 2,800 words, I examine said play with a combination of theory from Ferdinand de Saussure (signs, structure, and diachrony) and Jacques Derrida (différance, supplement). My analytical investigation examines how the implied supplemental past shaped the reality of Lear’s ‘love.’ This theoretical inquiry (aided by honorable mentions Alan Watts, Mircea Eliade—quoting Rudolf Otto, Jordan B. Peterson, and Lord Acton) reveals another level of the play’s significance.

A brief note: for the in-text citations like “1.1.56” in my opening paragraph, the numbers reference Act, Scene, and Line, respectively.

Enjoy!

Ungilding the Lily of Lear’s ‘Love’: A Diachronic Endeavor into Différance

Things are seldom as simple as they seem. In Shakespeare’s King Lear, Lear asks, “Which of you shall we say doth love us most” (1.1.56). He asks this of his three daughters–Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia. He intends to divide his kingdom between them (favoring her that ‘loves’ him most). This is where the story begins—a present that implies a past (or an effect that presupposes one or more causes). Lear’s ‘love’ signifies something “wholly other” (ganz andere) than the term currently denotes (Eliade 9). Where love is now probably best considered as an animating spirit that inspires good, true, and beautiful treatment of others, Lear’s ‘love’ has another meaning. His orbiters knew the meaning: flatter for favor. Lear’s ‘love’ is like a gilded lily—a love stripped of a key element by a veneer of feigned praise and the facilitation of that praise. To fully apprehend the gilded lily that Lear’s ‘love’ is, a diachronic endeavor into différance is required. One must consider the implied supplementary past to better understand the referenced literary present.

The following includes four parts. Part one (I) will be a consideration of the gilded lily. Part two (II) will be a definition of love. Part three (III) will be a definition of “diachronic endeavor,” “différance,” and “implied supplemental past.” Part four (IV) will be the diachronic endeavor into the différance that is the implied supplementary past itself. After an analytical quest into the implied supplemental past, we will better appreciate the present Shakespeare presents in the opening of King Lear.

I: The Gilded Lily

Gilding the lily derives from a paraphrase of a line in another Shakespeare play, King John (Gild the Lily)(4.2.9—15). In that play’s context, the phrase means “double pomp,” line 9, and “wasteful … ridiculous excess,” line 15. Addition to the already inherently beautiful is so unnecessary and excessive the activity is worthy of ridicule. We will consider further in the following lines.

A lily is an intricate and delicate flower with a fragile and ephemeral lifespan. It has a brittle stem and flimsy petals, which are easy to crush underfoot and susceptible to blemishing. Love is like a lily—complicated, pure, fleeting (as an emotion), and most importantly: sufficient without superficial additions.

Gold is weighty and durable. It is used for currency, art, jewelry, and so on. Gold can also be turned into gold leaf or paint and used to give otherwise lackluster things a shine. Flattery—which we will see King Lear facilitates and accepts—is like gold gilding. It’s a thin, feel-good sheen.

Gilding the lily crushes the life from its petals and stem, objectifying it and removing its essential vitality. Unnecessary addition of the superficial to the intrinsically valuable tends only to undermine said value. Why cover the beautiful with a film of another beautiful thing? Is flattery (feigned praise) love or trimming? It must be the latter. Waste not.

II: Defining Love

Before delving into the gilding that occurred in King Lear it is crucial to define what “love” (not Lear’s ‘love’) really means. Following a brief digression, will be an adequate—if not entirely comprehensive—definition. This next paragraph (said digression) is written purely for the express purpose of opening the subsequent section with: “Love is a thing.”

“Thing” is the fundamental ontological category of all that is within Being. Put another way, whatever is in the universe (physical or not, organic or not) is a thing. In his lecture entitled, The Real You, Watts states: “You are something that the whole universe is doing, in the same way that a wave is something that the whole ocean is doing.” You are, as a human being, engaged in human being (which connects, in one form or another, with all other avenues of being). Being includes all cosmoses, material and intangible, and all associated parts/processes. Basically, in the broadest possible sense, Being is everything, and we are each “an aperture through which the universe is looking at and exploring itself” (Watts 90). We divide things—aspects of Being—into categories via qualifiers like ‘material,’ ‘immaterial,’ ‘organic,’ ‘inorganic,’ and so on. Thus…

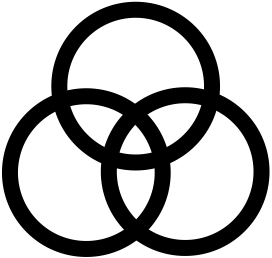

Love is a thing. Certain things have both essence and activity; love is one such thing. Things of this sort have fundamental elements—adding or removing core elements changes the thing in question (love might become lust, limerence, etc.). At an abstract level of analysis, love has three core elements. At a lower level of abstract analysis, there are two.

We speak of love in the abstract. At that level of analysis, love is necessarily simultaneously good, true, and beautiful (in activity and essence). Consider the following diagram:

At the center is love. The circles are goodness, truth, and beauty, respectively. The overlap between circles (excluding the middle) are evil, ignorance, and ugliness (evil the overlap opposite goodness, ignorant the overlap opposite truth, and so forth). There is no evil love—that would be lust. There is no ignorant love—that would be limerence or infatuation. There is no ugly love—that would be a contradiction in terms (beauty is in the eye of the beholder). There cannot be love where one or more core elements (goodness, truth, beauty) are absent. Flattery or feigned praise is hardly truthful. It might be good (for mollification) or even beautiful, but it isn’t true. Flattery isn’t sincere, it isn’t honest, it isn’t authentic. When you flatter (a tyrant, for example) or facilitate your being flattered (as a tyrant), definitionally you do not love. See the diagram below, similar to the one above but missing a key ingredient (truth):

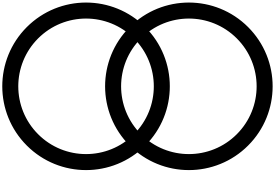

Moving to a lower level of analysis (from abstraction proper closer to actuality), love is partially acceptance and accountability. See the Taijitu diagram below:

Acceptance is Yin (black paisley and dot), accountability is Yang (white paisley and dot). Yin is mother to Yang (as excess chaos breeds desire for order, acceptance breeds desire for accountability), and Yang is father to Yin (as excess order breeds desire for chaos, accountability breeds desire for acceptance)(Peterson 344).

The argument follows: when you love, you accept your loved ones—loved ones being a phrase that includes yourself—for who they are. While you accept your loved ones, you also hold them accountable. Accepting the imperfection of loved ones (including yourself) and employing accountability (holding loved ones to who they could be, if they were who they should be) is the essence of love in action. Without acceptance, there can be no love—try rejecting yourself or other loved ones and see how that works out. Is letting a loved one get worse, rather than better, loving? If you love someone, be kind, not nice. It might be nice to avoid conflict and let loved ones fall, but it is not kind. Appeasing another’s ego (like that of the tyrant) is not loving. Encouraging ego appeasement (as a tyrant) is not loving either.

See the diagram below, similar to the Taijitu but missing accountability:

Good, true, and beautiful essence/activity (love) is lustrous, intricate, and delicate; the same is true of accepting and holding accountable. Love at these levels of analysis needs no veneer, no golden guise, no trimming. When, for example, you flatter or facilitate such superficial behavior, you remove truth and accountability—and thus love—from the equation.

III: Defining Diachrony, Différance, and More

Now that we have an understanding of love and how flattery can make love become like a gilded lily, it is time to explain this “diachronic endeavor into the différance that is the implied supplemental past.”

“Diachronic endeavor” here refers to an investigation into what shaped meaning as we currently understand it. Exploring the evolution of Lear’s notion of love is a diachronic analysis. For signifiers (‘love’ as Lear uses it, for instance), “everything that has to do with [their] evolution is diachronic” (Saussure 220). The exploration of events that shaped ‘love,’ as Lear uses it, is a form of said analysis. Previous context facilitates present understanding. Now, that previous context is, in fact, not in the play. This is where différance comes into play. By “différance” we mean the implied supplementary past. “Supplement [is] another name for différance” (Derrida 618). Via the différance (supplement) of a moment we find more meaning than initially presents itself. The essentially nonexistent (implied, not written) series of events which brought Lear and his orbiters into accord supplements our understanding of the play’s significance. It is also a causal factor in the present Shakespeare presents in the play’s opening (see Lear’s question to his daughters at the top). The shared understanding of Lear’s ‘love’ was acquired in the implied supplemental past. With our terms defined, let us embark on a diachronic endeavor into the différance that is the implied supplemental past. This endeavor will reveal the full weight of the moment by illuminating meaning in a manner inaccessible absent employment of the aforementioned perspectives.

IV: Diachronic Endeavor into Différance

Shakespeare did not give us explicit insight into the interactions which precipitated (caused) Lear’s ‘love’ as understood and acted upon by his daughters/Kent; he gave us implicit insight alongside the effect. Lear’s orbiters knew to appeal to Lear’s ego, and this knowledge came from before the beginning of the play.

We know this for several reasons.

Goneril and Regan confirm that Lear, even in the “best and soundest of his time” was “but rash,” acknowledging this is Lear’s “long-engraffed” (habitual) state—one that resulted in Lear’s banishment of Cordelia and Kent (1.1.339—43)(Crystal). Lear is known to be… Touchy, as it were.

Kent’s comportment reinforces the notion that Lear’s orbiters had foreknowledge of his touchiness. Kent qualifies and hedges before speaking (to which Lear impatiently responds: “the bow is bent and drawn. Make from the shaft”), and even mentions Lear’s “rashness” (1.1.160—169).

In addition to Kent’s action early in the play, he proves that Lear’s ‘love’ is Lear-specific and Lear-initiated. The game of flattery may be the byproduct of Lear’s setting or social circumstance (i.e., being king). Although it might not have explicit historical reference within the play, it is specific to and initiated by Lear. This is seen as Lear and Kent play the game again. A disguised Kent trips Oswald, and Lear says, “thou serv’st me, and I’ll love thee” (1.4.88). Kent plays the game of Lear’s ‘love’ and returns to favor. Lear’s ‘love’ is a game of flattery for favor. Kent knows how to play. He has played before.

Cordelia’s defiance despite Goneril and Regan’s capitulation both blurs and clarifies our contention. She is bound to the linguistic community of her father’s court by blood. She understands love proper (love as described in Part Two). We argue she also understands Lear’s ‘love.’ Even if her knowledge did not—as we know it did for Kent, Goneril, and Regan—originate prior to the play’s opening, it came prior to her defiance. The sanguine and saccharine overtures of her older sisters tipped her off—evidenced in her asides as said overtures occur (1.1.68, 85—87). Despite the threat of consequence (even if only intuitively apparent to Cordelia) Cordelia refuses to sacrifice her sophisticated understanding of love for material gain, for security, or even for proximity to her unloving loved one, replying to Lear, “Nothing, my Lord” (1.1.196). This silence (lack of flattery) speaks volumes that ripple throughout the play (as we will see).

Lear’s ‘love’ is an equation, plug incorrect (by Lear’s standards) action into the equation, and find yourself punished. Goneril, Regan, and Kent know this. Cordelia, in faithful bravery, proves her love despite this and is subjected to Lear’s ‘love.’ She breaks the cycle as a truthful individual, and, with the help of Kent, Lear’s ‘love’ is eventually ended—as one of those ripple-effects, replaced with the real thing (if you can call love a thing, of course)(5.3.9).

Thus, one aspect of the implied past (which supplements understanding of the orbiter’s understanding in the present Shakespeare presents in his opening act) is foreknowledge of the game of Lear’s ‘love.’ In addition to the fact that humans “make signs … which [represent] the present in its absence”—the implication of that implied supplementary past is that moment by moment Lear’s ‘love’ became clarified to himself and those in his orbit (Derrida 591). Lear’s orbiters (those who have witnessed the game play out with Kent/Goneril/Regan) know he requires service or flattery for his love. The game did not arise out of nothing (“nothing can be made of nothing”)(1.4.136). Lear’s ‘love’ was clarified moment by moment in the past implied by the present (the time before the beginning of the play). Furthermore, we can conclude the gilding (while apparent in Goneril/Regan/Kent’s actions in the play) began prior to the play, in the implied past. The rules of the game precede Goneril, Regan, and Kent’s properly playing it—as evidenced by their words and behavior in the play.

Remember Lear’s question at the top? How can one play a game without understanding the rules? Kent is able to get back into Lear’s good graces because he knows how the game (specific to and spearheaded by Lear) is played. Goneril and Regan are able to give Lear what he wants–on the spot–and get what they want because they know how the game is played. An octogenarian, Lear’s patterns have had time to repeat (4.7.68). He is a touchy tyrant—flattering the touchy tyrant is the way to ensure security and success (with the exception of the Fool, an exception that proves the rule).

It is not merely Lear who constructs Lear’s ‘love.’ His community (his family and his court) enables and facilitates its establishment. “The individual [alone] does not have the power to change a sign in any way once it has become established in the linguistic community” (Saussure 209). Cordelia’s defiance does not effect change (not initially). She suffers the consequences. Over time, Lear’s system (him and his orbiters) make “love” synonymous with “flatter Lear to avoid his wrath and secure resources/favor.” This establishment was eventually overthrown as Lear develops and encounters others who communally influence the sign’s dismantling—again, ripple effects, but it was too late (5.3.369).

The present implies the past. The particularities of the present presented imply a specific past. That specific past is a community of speakers gilding the lily of Lear’s ‘love’ (a community that at least includes Lear, his eldest daughters, and Kent). Removing truth, removing accountability, love is morphed into Lear’s ‘love.’ Without considering the implied supplementary past, the magnitude of that community’s behavior is underappreciated.

They (Lear’s orbiters) do it to themselves. They all play the game of Lear’s ‘love,’ gilding the lily of love (by flattering and serving Lear’s ego, positively reinforcing his behavior), until they eventually—in objectifying love—crush it. Without doing a diachronic dive into the différance that is the implied supplementary past, one does not fully realize the bravery of Cordelia, the cunning of Kent, the duplicity of Goneril and Regan, and the ego of Lear. Furthermore, one might miss the community’s complicity in creating and sustaining the game of Lear’s ‘love’ without this deeper analysis. Lear’s ‘love’ is like a lily, gilded by him and his community. It is a game whose rules were defined and refined every time an orbiter flattered or served Lear’s ego for favor or material gain.

The equation of Lear’s ‘love’ has been run before and its function is understood. It is a game. Play it well (flatter Lear) and favor befalls you. Play it poorly…

Kent plays the game wrong (out of love of Cordelia and Lear), but returns to favor by exploiting the rules of the game (a pragmatic argument against the touchy tyrant’s tendencies).

Cordelia loves, and—while initially being subjected to the game—is eventually loved back.

King Lear learns from his prideful fall, but not soon enough.

Lear’s eldest daughters take advantage, gain material resources, and lose love, corrupted by power (they are given land, while Cordelia is not, and eventually, at the expense of love, acquire control of the whole kingdom)(Acton 1887).

On this last point (losing love), the problem with intentionally unlovely behavior is, of course, you must keep your own company. How appealing is the idea of keeping the company of casuists? Not very. How can you trust another if you know the depths of the abyss of indifference? Hardly with ease.

Conclusion

After embarking on a diachronic endeavor into the différance that is the implied supplemental past, one discovers the causes which led to the effect (the opening of Shakespeare’s King Lear). This discovery adds significance by deepening our understanding of the play’s aims, highlighting what can unfold under particular circumstances. An aspect of those circumstances is the set of circumstantial causal factors (including historical context). Consider the cause(s) to better understand the breadth of the effect’s significance. Would you like to better know why Shakespeare wrote King Lear? Consult the implied supplementary past.

Can you tell what authors show? Analysis of the sort done so far will assist you. This sort of analysis (the Saussure/Derrida combination, the additions from other thinkers, and our personal philosophical explication) can be applied to all literary works. The variety of significance acquired above is latent in all literature. Uncovering such meaning is up to us.

Through diachronic analysis and différance we uncover some of the complex causes that shape the behavioral dynamics in King Lear. This enhances our interpretation of the play by revealing the evolution of Lear’s ‘love.’ This increases the play’s significance.

Consider: things are seldom as simple as they seem.

Superar la adversidad.

Works Cited

Acton, John Emerich Edward Dalberg, Lord. Acton-Creighton Correspondence. Online Library of Liberty, Liberty Fund, https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/acton-acton-creighton-correspondence.

Crystal, David, and Ben Crystal. “Glossary: Headword - ‘Long-ingraffed’.” Shakespeare's Words, www.shakespeareswords.com/Public/GlossaryHeadword.aspx?headwordId=19349.

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1959.

“Gild the Lily.” Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/word-of-the-day/gild%20the%20lily-2008-04-04.

Peterson, Jordan B. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief. Routledge, 1999.

De Saussure, Ferdinand. Literary Theory: An Anthology, edited by Rivkin, Julie, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2017, p. 220. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ric-ebooks/detail.action?docID=7103984.

Shakespeare, William. King John. Edited by Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles, Folger Shakespeare Library, www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/king-john/read/4/2/?q=gild#line-4.2.9.

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Edited by Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles, Folger Shakespeare Library, www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/king-lear/read/.

Watts, Alan. Still the Mind: An Introduction to Meditation. New World Library, 2000.

Watts, Alan. “The Real You.” Lecture, alanwatts.org, 1971.

Shakespeare and analysis? Count me in!

Great job on this!